Munda languages

| Munda | |

|---|---|

| Mundaic | |

| Geographic distribution | Indian subcontinent |

| Ethnicity | Munda peoples |

| Linguistic classification | Austroasiatic

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Munda |

| Subdivisions | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | mun |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | mund1335 |

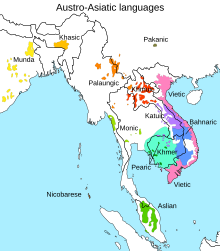

Map of areas with significant concentration of Munda speakers | |

The Munda languages are a group of closely related languages spoken by about nine million people in India, Bangladesh and Nepal.[1][2][3] Historically, they have been called the Kolarian languages.[4] They constitute a branch of the Austroasiatic language family, which means they are more distantly related to languages such as the Mon and Khmer languages, to Vietnamese, as well as to minority languages in Thailand and Laos and the minority Mangic languages of South China.[5] Bhumij, Ho, Mundari, and Santali are notable Munda languages.[6][7][1]

The family is generally divided into two branches: North Munda, spoken in the Chota Nagpur Plateau of Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Bihar, Odisha and West Bengal, as well as in parts of Bangladesh and Nepal, and South Munda, spoken in central Odisha and along the border between Andhra Pradesh and Odisha.[8][9][1]

North Munda, of which Santali is the most widely spoken and recognised as an official language in India, has twice as many speakers as South Munda. After Santali, the Mundari and Ho languages rank next in number of speakers, followed by Korku and Sora. The remaining Munda languages are spoken by small, isolated groups, and are poorly described.[1]

Characteristics of the Munda languages include three grammatical numbers (singular, dual and plural), two genders (animate and inanimate), a distinction between inclusive and exclusive first person plural pronouns, the use of suffixes or auxiliaries to indicate tense,[10] and partial, total, and complex reduplication, as well as switch-reference.[11][10] The Munda languages are also polysynthetic and agglutinating.[12][13] In Munda sound systems, consonant sequences are infrequent except in the middle of a word.

Origin

[edit]Many linguists suggest that the Proto-Munda language probably split from proto-Austroasiatic somewhere in Indochina.[citation needed] Paul Sidwell (2018) suggests they arrived on the coast of modern-day Odisha about 4000–3500 years ago (c. 2000 – c. 1500 BCE) and spread after the Indo-Aryan migration to the region.[14][15]

Rau and Sidwell (2019),[16][17] along with Blench (2019),[18] suggest that pre-Proto-Munda had arrived in the Mahanadi River Delta around 1,500 BCE from Southeast Asia via a maritime route, rather than overland. The Munda languages then subsequently spread up the Mahanadi watershed. 2021 studies suggest that Munda languages impacted Eastern Indo-Aryan languages.[19][20]

Classification

[edit]Munda consists of five uncontroversial branches (Korku as an isolate, Remo, Savara, Kherwar, and Kharia-Juang). However, their interrelationship is debated.

Diffloth (1974)

[edit]The bipartite Diffloth (1974) classification is widely cited:

- Munda

- North Munda

- South Munda

Diffloth (2005)

[edit]Diffloth (2005) retains Koraput (rejected by Anderson, below) but abandons South Munda and places Kharia–Juang with the northern languages:

Anderson (1999)

[edit]Gregory Anderson's 1999 proposal is as follows.[21]

However, in 2001, Anderson split Juang and Kharia apart from the Juang-Kharia branch and also excluded Gtaʔ from his former Gutob–Remo–Gtaʔ branch. Thus, his 2001 proposal includes 5 branches for South Munda.

Anderson (2001)

[edit]Anderson (2001) follows Diffloth (1974) apart from rejecting the validity of Koraput. He proposes instead, on the basis of morphological comparisons, that Proto-South Munda split directly into Diffloth's three daughter groups, Kharia–Juang, Sora–Gorum (Savara), and Gutob–Remo–Gtaʼ (Remo).[23]

His South Munda branch contains the following five branches, while the North Munda branch is the same as those of Diffloth (1974) and Anderson (1999).

- Note: "↔" = shares certain innovative isoglosses (structural, lexical). In Austronesian and Papuan linguistics, this has been called a "linkage" by Malcolm Ross.

Sidwell (2015)

[edit]Paul Sidwell (2015:197)[24] considers Munda to consist of 6 coordinate branches, and does not accept South Munda as a unified subgroup.

Phonology

[edit]Consonants, vowels, and syllable

[edit]The Munda languages share a similar set of consonants with the Eastern Austroasiatic languages. Inherited Austroasiatic glottalized stop and nasalized release of Munda are noteworthy unique phonotactic features in South Asia. Munda generally have fewer vowels (between 5 to 10) than comparatively the Eastern Austroasiatics, still more than that of Indo-Aryan and Dravidian.[25] Like any other Austroasiatic languages, the Munda languages make extensive uses of diphthongs, triphthongs. Larger vowel sequences may be found, with an extreme example of Santali kɔeaeae meaning ‘he will ask for him’.[26] Most Munda languages have registers but lack tones with an exception of Korku who has acquired two tones from South Asian: an unmarked high and a marked low.[27][28] The general syllable shape is (C)V(C),[29] and the preference structure for disyllables is CV.CV. South Munda displays tendency toward initial clusters, CCVC word shape, with best regards are manifested in the Gtaʔ case.[30]

Word prominence

[edit]Donegan & Stampe (2004) posited overarching assumptions that all Munda languages have completely redesigned their word prosodic structure from proto-Austroasiatic sesquisyllablic, iambic and reduced vowel to Indic norms of trochaic, falling rhythm, stable or assimilationist consonants and harmonised vowels, making them oppose to Eastern Austroasiatic languages at almost every level. Sidwell & Rau (2014) criticized Donegan & Stampe, pointing out that the overall picture appears much more complicated and diverse, and that generalizations of Donegan & Stampe are not supported by the instrumental data of the various Munda languages.[31] Peterson (2011b) describes word-rising in monosyllables and second syllable prominence in Kharia content words. The presence of clitics and affixes even does not drive Kharia word prosodic structure to that of a trochaic and falling system Peterson (2011b). Osada (2008) reports final syllable stress in all but CVC.CV stems in Mundari.[32] Horo & Sarmah (2015), Horo (2017) and Horo, Sarmah & Anderson (2020) found that the Sora disyllables are always iambic, reduced first syllable vowel space, and second syllable prominence.[33][34] Even CV.CCə words show final syllable prominence. Horo & Sarmah (2015) note that the Sora vowels of the first syllables are “centralized” while vowels in the second syllables are more representative of the canonical vowel space. Ghosh (2008) describes the Santali prosody that “stress is always released in the second syllable of the word regardless of whether it is an open or a closed syllable.”[35] His analysis has been confirmed by Horo & Anderson (2021), whose acoustic data clearly shows that the Santali second syllable is always the prominent syllable with greater intensity of stress and a rising contour.[36] Zide (2008) reports that in Korku, the final syllable is heavier than the initial syllable, and within a disyllable, stress is preferentially released at the final syllable.[37] Munda overall appears to have bi-moraic word constraint patterns that they inherited from proto-Austroasiatic. Again, Donegan & Stampe (2004) claim on rhythmic holism does not conform with data presented by individual Munda languages.[38]

Morphology

[edit]Morphologically, both North and South Munda subgroups mainly focus on the head or the verb, thus they are primarily head-marking, in contrast to dependent-marking Indo-European and Dravidian families.[39] As a result, nominal morphology is less complex than verbal morphology.[40][41] Case markers on nominals to show syntactic alignments, i.e. nominative-accusative, ergative-absolutive, are largely absent or not systematically developed among the Munda languages except Korku. Relation between subject and object in clause is mainly conveyed through verbal referent indexation and word order. At clause/sentence level, Munda languages are head-final, but internally head-first in referent indexation, compounds, and noun incorporation verb complexes.[42][43] In word derivation, besides their own innovative methods, the Munda languages maintain Austroasiatic methods in forms of derivational infixes and prefixes.[44] Some languages retain a dative-oblique prefix a-.[45]

North Munda

[edit]The North Munda subgroup is split between Korku and the fourteen Kherwarian languages.

Kherwarian languages

[edit]Kherwarian is a large language continuum with speakers extending west to east from the Indian states of Uttar Pradesh to Assam, north to south from Nepal to Odisha. The fourteen Kherwarian languages are Asuri, Birhor, Bhumij, Koda, Ho, Korwa (Korowa), Mundari, Mahali, Santali, Turi, Agariya, Bijori, Koraku, and Karmali, with the total number of speakers surpassing ten million (2011 census). Kherwarian are often highlighted due to their elaborate and complex templatic and pronominalized predicate are so pervasive that it is obligatory for the verb to encode TAM, valency, voices, possessive, transitivity, clear distinction between exclusive and inclusive first persons, and index with all arguments, including non-arguments like possessors.

| core | +1 | +2 | +3 | +4 | +5 | +6 | +7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| verb stem (+ infixes) | APPL | TAM | voice/valency | POSS | OBJ | IND/FIN | SUBJ |

| Kherwarian languages | Examples |

|---|---|

| Santali | gəi=ko cow=3PL.SUBJ idi-ke-d-e-tiŋ-a take-AOR-TR-3SG.OBJ-1SG.POSS-FIN 'they took my cow' |

| Mundari | maŋɖi food seta-ko=ŋ dog-PL=1SG.SUBJ om-a-d-ko-a give-BEN-TR-3PL.OBJ-FIN 'I gave the food to the dogs' |

| Ho | abu 1PL hotel-te=bu hotel-ABL=1PL.SUBJ senoʔ-tan-a=bu go-PROG-FIN=1PL.SUBJ 'we are going to/from the hotel' |

| Asuri | holate yesterday iŋ I huɽu paddy ir=iŋ cut=1SG.SUBJ sen-tehin-e-a=iŋ go-TAM-INTR-FIN=1SG.SUBJ yesterday I went to cut rice |

| Bhumij | hɔɽɔta-ke man-OBJ lel-(dʒaʔt)dʒi-a=iŋ see-ASP.(TR)-FIN=1SG.SUBJ 'I am looking at the man' |

| Koda | ka=m NEG=2SG.SUBJ äm-ta-t-in-a=m give-ASP-TR-1SG.OBJ-FIN=2SG.SUBJ 'you didn't give me (it)' |

| Korwa | mene-m NEG-2SG.SUBJ em-ga-d-iñ-a given-ASP-TR-1SG.OBJ-FIN 'you haven't given to me' |

| Turi | ini-ke he-DAT/ACC ka=ko NEG=3PL.SUBJ em-a-i-ke-n-a give-BEN-3SG.OBJ-ASP-INTR-FIN 'They didn’t give him' |

| Birhor | iŋ 1SG am=ke 2SG=OBJ nel-me-kanken=ĩ see-2SG.OBJ-IMPERF=1SG.SUBJ 'I was looking at you' |

Noun incorporation, which has been described as an ancestral Munda morphological feature and is essential to the grammar of other South Munda languages such as Sora, but Kherwarians appear to have lost noun incorporation altogether. Nevertheless, rare surviving examples of noun incorporation could be found in some Kherwarian archaic registers and oral literature.

tʄeɳe-ko

bird-PL

nam-oɽaʔ-ta-n-a=ko

find-house-ASP-INTR-FIN=3PL.SUBJ

'the birds are getting into their nests (and trying to lay an egg)'

Korku

[edit]Unlike the Kherwarian languages with their complex verbal morphology, the Korku verb is moderately simple with modest amount of synthesis.[46] Korku lacks person/number indexing of subject(s)/actor (except third persons of locative copulas and nominal predicates in the locative case) and lack of independent present/future tense markers.[47] Korku present/future tenses rely on the finitizer suffix -bà.[48] Present/Future tense negation can be located in either preverbal or post-verbal, but past tense negation is marked by suffix -ᶑùn.[49]

Many Korku auxiliary verbs are borrowed from Indo-Aryan. The auxiliary predicate will take TAM, voice, finiteness suffixes for the verb. Such an example would be ghaʈa- meaning 'to manage to, to find a way to' serves as the acquisitive.[50]

South Munda

[edit]Compared to North Munda, the South Munda languages are even more divergent with fewer shared morphological traits. Even the classification of Munda languages figures out that South Munda does not seem to exist as a valid taxon. However, South Munda languages retain many notable characteristics of the original proto-Munda such as prefix slots, scope-ordering of referent indexation, thus they represent the less restructured morphology of Munda, reflecting the older proto-Munda as well as proto-Austroasiatic structures.[51][52]

Kharia

[edit]In Kharia, subject markers index not only dual/plural exclusive/inclusive but also honorific status. Objects are not marked in the verb in per se. They are marked, instead, by oblique case =te.

There is a reduplicated free-standing form of each finite verb that behaves differently from simple verb stem. In the predicate, reduplicated free-standing form never marks TAM and person. Because of this, the free-standing form is used in subordination, an attributive function corresponding more or less to relative clauses. The infinitive verb form is marked by =na. The infinitive can serve as nominalizer, too: jib=na=te ‘touching’.

| Simple verb root | Free-standing form | |

|---|---|---|

| live | borol | borol |

| open | ruʔ | ruʔruʔ |

| see | yo | yoyo |

Similar to Hindi and Sadani, Kharia has made a calque to form sequential converbs (conjunctive participles) kon (derived from ikon, ‘do’). They denote the completion of an action before another begins.

The negation particle um attaches or fuses person/number/honorific of the subject argument.

Juang

[edit]Juang exhibits nominative-accusative alignment with unmarked subject/agents and marked objects or patients.

Being a pro-drop language, Juang has a tendency or obligatory of indexing both two core arguments in a transitive predicate. If the arguments are not omitted, referent indexation is largely optional. Juang has a fairly complex TAM system that is often divided into two sets: I for transitive verbs and II for intransitive verbs. The verb ‘be’ usually does not show up in the present tense and with the presence of a predicate adjective in sentences.

Abu

Abu

muintɔ

one

dakotoro

doctor

'Abu is a doctor'

There are two types of negation markers: Pronominal negation markers are specific for person/number of subject or object arguments. General negation markers, such as -jena, supplant lack of first person singular negative. Negatives are ambifixative but mainly prefer to precede the verb stem. There are double negations, i.e. combinations of two negatives. The negated verb may reduplicate itself.

apa

2DU

a-ma-ɉim-ke

2DU.SUBJ-NEG-eat-PRES

ete

because

ain

1SG

kikib

RED~do

ɉena

NEG.COP

'Because you don’t eat (it), I didn’t do it'

Noun incorporation is fossilized in lexical compounds and words like body parts being combined with the verb ‘wash’. Notice that the head precedes the incorporated object, as opposed to head-final position in normal clauses.

am

you

am-a

you-GEN

itim-de

hand:2-DEF

mi-gui-di-agan

2SG.SUBJ-wash-hand-PST

'You wash your hand'

Munda lexicon and lexical relation with other Indian language families

[edit]Despite some influence from neighboring languages, the Munda languages generally maintain a solid Austroasiatic and Munda base vocabulary.[53][54] The most extreme case is from Sora which has zero foreign phonemes.[53] Agricultural-related words from proto-Austroasiatic are widely shared (Zide & Zide 1976). Words for domesticated animal and plant species like dogs, millet, chicken, goat, pig, rice are shared. There are even specific terms for husked uncooked rice vs cooked rice vs rice field, as well as shared words used in rice production and processing like 'mortal', 'pestle', 'paddy', 'sow', 'grind/ground'. The majority of loan words from Indo-Aryan to Munda are quite recent and mostly came from Hindi. The Southern languages like Gutob have received considerable Dradivian lexical influence. A very small number of lexemes seem to be shared between Munda and Tibeto-Burman, probably reflecting earlier contact between two groups.[55]

It is clear that hundreds of non-Indo-European words in Vedic Sanskrit that Kuiper (1948) attributed to Munda has been rejected through careful analysis.[55] Except for words like ‘cotton’, there is a surprising absence of Sanskrit and Middle Indian borrowings of animals & plants from Munda. Scholars believe that the Munda tribes typically occupied a marginalized and lowly socioeconomic position in the Hinduized society of Vedic South Asia, or did not participate in the Hindu caste system and had barely any contact with Hindus at all. Witzel (1999) and Southworth (2005) proposed that the early non-Indo-European words with ka- prefix in Vedic Sanskrit belonged to a hypothetic ‘Para-Munda substratum’ that he believed to be part of the Harappan language.[56] This would imply that Austroasiatic speakers might have penetrated as far as the Panjab and Afghanistan in the early second millennium BC, whereas Osada (2009) refuted Witzel that those words might have been, in fact, Dravidian compounds.

Distribution

[edit]| Language name | Number of speakers (2011) | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Korwa | 28,400 | Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand |

| Birjia | 25,000 | Jharkhand, West Bengal |

| Mundari (inc. Bhumij) | 1,600,000 | Jharkhand, Odisha, Bihar |

| Asur | 7,000 | Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Odisha |

| Ho | 1,400,000 | Jharkhand, Odisha, West Bengal |

| Birhor | 2,000 | Jharkhand |

| Santali | 7,400,000 | Jharkhand, West Bengal, Odisha, Bihar, Assam, Bangladesh, Nepal |

| Turi | 2,000 | Jharkhand |

| Korku | 727,000 | Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra |

| Kharia | 298,000 | Odisha, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh |

| Juang | 30,400 | Odisha |

| Gtaʼ | 4,500 | Odisha |

| Bonda | 9,000 | Odisha |

| Gutob | 10,000 | Odisha, Andhra Pradesh |

| Gorum | 20 | Odisha, Andhra Pradesh |

| Sora | 410,000 | Odisha, Andhra Pradesh |

| Juray | 25,000 | Odisha |

| Lodhi | 25,000 | Odisha, West Bengal |

| Koda | 47,300 | West Bengal, Odisha, Bangladesh |

| Kol | 1,600 | West Bengal, Jharkhand, Bangladesh |

Reconstruction

[edit]The proto-forms have been reconstructed by Sidwell & Rau (2015: 319, 340–363).[57] Proto-Munda reconstruction has since been revised and improved by Rau (2019).[58][59]

Writing systems

[edit]The following are current used alphabets of Munda languages.

- Mundari Bani (Mundari alphabet)[60]

- Ol Chiki (Santali alphabet)[61]

- Ol Onal (Bhumij alphabet)[62]

- Sorang Sompeng (Sora alphabet)[63]

- Warang Citi (Ho alphabet)[64]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d Anderson, Gregory D. S. (29 March 2017), "Munda Languages", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.37, ISBN 978-0-19-938465-5

- ^ Hock, Hans Henrich; Bashir, Elena, eds. (23 January 2016). The Languages and Linguistics of South Asia. doi:10.1515/9783110423303. ISBN 9783110423303.

- ^ "Santhali". Ethnologue. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Anderson, Gregory D. S. (8 April 2015). The Munda Languages. Routledge. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-317-82886-0.

- ^ Bradley (2012) notes, MK in the wider sense including the Munda languages of eastern South Asia is also known as Austroasiatic

- ^ Pinnow, Heinz-Jurgen. "A comparative study of the verb in Munda language" (PDF). Sealang.com. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Daladier, Anne. "Kinship and Spirit Terms Renewed as Classifiers of "Animate" Nouns and Their Reduced Combining Forms in Austroasiatic". Elanguage. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Bhattacharya, S. (1975). "Munda studies: A new classification of Munda". Indo-Iranian Journal. 17 (1): 97–101. doi:10.1163/000000075794742852. ISSN 1572-8536. S2CID 162284988.

- ^ "Munda languages". The Language Gulper. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ a b Kidwai, Ayesha (2008), "Gregory D. S. Anderson the Munda Verb: Typological Perspectives", Annual Review of South Asian Languages and Linguistics, Trends in Linguistics. Studies and Monographs [TiLSM], Berlin, New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 265–272, doi:10.1515/9783110211504.4.265, ISBN 978-3-11-021150-4

- ^ Anderson, Gregory D. S. (7 May 2018), Urdze, Aina (ed.), "Reduplication in the Munda languages", Non-Prototypical Reduplication, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 35–70, doi:10.1515/9783110599329-002, ISBN 978-3-11-059932-9

- ^ Donegan, Patricia Jane; Stampe, David. "South-East Asian Features in the Munda Languages". Berkley Linguistics Society.

- ^ Jenny, Weber & Weymuth (2014), p. 14.

- ^ Sidwell, Paul. 2018. Austroasiatic Studies: state of the art in 2018. Presentation at the Graduate Institute of Linguistics, National Tsing Hua University, Taiwan, 22 May 2018.

- ^ "Sidwell AA studies state of the art 2018.pdf". Google Docs. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Rau, Felix; Sidwell, Paul (2019). "The Munda Maritime Hypothesis". Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society (JSEALS). 12 (2). hdl:10524/52454. ISSN 1836-6821.

- ^ Rau, Felix and Paul Sidwell 2019. "The Maritime Munda Hypothesis." ICAAL 8, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 29–31 August 2019. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3365316

- ^ Blench, Roger. 2019. The Munda maritime dispersal: when, where and what is the evidence?

- ^ Ivani, Jessica K; Paudyal, Netra; Peterson, John (2021). Indo-Aryan – a house divided? Evidence for the east–west Indo-Aryan divide and its significance for the study of northern South Asia. Journal of South Asian Languages and Linguistics, 7(2):287–326. doi:10.1515/jsall-2021-2029

- ^ John Peterson (October 2021). "The spread of Munda in prehistoric South Asia -the view from areal typology To appear in: Volume in Celebration of the Bicentenary of Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute (Deemed University)". Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ Anderson, Gregory D.S. (1999). "A new classification of the Munda languages: Evidence from comparative verb morphology." Paper presented at 209th meeting of the American Oriental Society, Baltimore, MD.

- ^ Anderson, G.D.S. (2008). ""Gtaʔ" The Munda Languages. Routledge Language Family Series. London: Routledge. pp. 682–763". Routledge Language Family Series (3): 682–763.

- ^ Anderson, Gregory D S (2001). A New Classification of South Munda: Evidence from Comparative Verb Morphology. Indian Linguistics. Vol. 62. Poona: Linguistic Society of India. pp. 21–36.

- ^ Sidwell, Paul. 2015. "Austroasiatic classification." In Jenny, Mathias and Paul Sidwell, eds (2015). The Handbook of Austroasiatic Languages. Leiden: Brill.

- ^ Sidwell & Rau (2014), p. 314.

- ^ Anderson (2014), p. 375.

- ^ Zide (2008), p. 258.

- ^ Sidwell & Rau (2014), p. 318.

- ^ Sidwell & Rau (2014), p. 312.

- ^ Sidwell & Rau (2014), p. 320.

- ^ Sidwell & Rau (2014), p. 321.

- ^ Osada (2008), p. 104.

- ^ Horo, Luke; Sarmah, Priyankoo (2015). "Acoustic analysis of vowels in Assam Sora". North East Indian Linguistics. 7: 69–88.

- ^ Horo, Luke; Sarmah, Priyankoo; Anderson, Gregory D. S. (2020). "Acoustic phonetic study of the Sora vowel system". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 147 (4): 3000–3011. doi:10.1121/10.0001011.

- ^ Anderson (2014), p. 379.

- ^ Horo, Luke; Anderson, Gregory D. S. (2021). "Towards a prosodic typology of Kherwarian Munda languages: Santali of Assam.". In Alves, Mark J.; Sidwell, Paul (eds.). Papers from the 30th Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society. JSEALS Special Publications 8. University of Hawai'i Press. pp. 298–317.

- ^ Zide (2008), p. 260.

- ^ Hildebrandt & Anderson (2023), p. 559.

- ^ Donegan & Stampe (2004), p. 13.

- ^ Sidwell & Rau (2014), p. 311.

- ^ Anderson (2014), p. 381.

- ^ Donegan & Stampe (2002), p. 115–116.

- ^ Jenny (2020), p. 24.

- ^ Anderson (2014), p. 382.

- ^ Anderson (2014), p. 383.

- ^ Zide (2008), p. 270.

- ^ Zide (2008), p. 271–272.

- ^ Zide (2008), p. 273.

- ^ Zide (2008), p. 279–280.

- ^ Zide (2008), p. 284.

- ^ Jenny (2020), p. 25.

- ^ Rau (2020), p. 229.

- ^ a b Donegan & Stampe (2004), p. 12.

- ^ Anderson (2014), p. 402.

- ^ a b Anderson (2014), p. 403.

- ^ Witzel, M. (August 1999). "Substrate languages in old Indo-Aryan". EJVS. 5 (1): 1–67. cf. reprint in: "[no title cited]". International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics (IJDL) (1). sqq. 2001.

- ^ Sidwell, Paul and Felix Rau (2015). "Austroasiatic Comparative-Historical Reconstruction: An Overview." In Jenny, Mathias and Paul Sidwell, eds (2015). The Handbook of Austroasiatic Languages. Leiden: Brill.

- ^ Rau, Felix. (2019). Advances in Munda historical phonology. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3380908

- ^ Rau, Felix. (2019). Munda cognate set with proto-Munda reconstructions (Version 0.1.0) [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3380874

- ^ "Atlas of Endangered Alphabets: Indigenous and minority writing systems, and the people who are trying to save them". 19 January 2024. Retrieved 4 February 2025.

- ^ "Santali language and alphabets". www.omniglot.com. Retrieved 4 February 2025.

- ^ "Ol Onal alphabet". www.omniglot.com. Retrieved 4 February 2025.

- ^ "Atlas of Endangered Alphabets: Indigenous and minority writing systems, and the people who are trying to save them". 30 November 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2025.

- ^ "Warang Citi alphabet". www.omniglot.com. Retrieved 4 February 2025.

General references

[edit]- Diffloth, Gérard (1974). "Austro-Asiatic Languages". Encyclopædia Britannica. pp. 480–484.

- Diffloth, Gérard (2005). "The contribution of linguistic palaeontology to the homeland of Austro-Asiatic". In Sagart, Laurent; Blench, Roger; Sanchez-Mazas, Alicia (eds.). The Peopling of East Asia: Putting Together Archaeology, Linguistics and Genetics. RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 79–82.

Further reading

[edit]- Anderson, Gregory D S (2007). The Munda verb: typological perspectives. Trends in linguistics. Vol. 174. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-018965-0.

- Anderson, Gregory D S, ed. (2008). Munda Languages. Routledge Language Family Series. Vol. 3. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-32890-6.

- Anderson, Gregory D. S. (2015). "Prosody, phonological domains and the structure of roots, stems and words in the Munda languages in a comparative/historical light". Journal of South Asian Languages and Linguistics. 2 (2): 163–183. doi:10.1515/jsall-2015-0009. S2CID 63980668.

- Anderson, Gregory D. S.; Boyle, John P. (2002). "Switch-Reference in South Munda". In Macken, Marlys A. (ed.). Papers from the 10th Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society (PDF). Tempe, AZ: Arizona State University, South East Asian Studies Program. pp. 39–54. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2015.

- Brown, E. K., ed. (2006). "Munda Languages". Encyclopedia of Languages and Linguistics. Oxford: Elsevier Press.

- Donegan, Patricia J.; Stampe, David (1983). "Rhythm and the holistic organization of linguistic structure". Chicago Linguistic Society. 19 (2): 337–353.

- Donegan, Patricia; Stampe, David (2002). "South-East Asian Features in the Munda Languages: Evidence for the Analytic-to-Synthetic Drift of Munda". In Chew, Patrick (ed.). Proceedings of the 28th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, Special Session on Tibeto-Burman and Southeast Asian Linguistics, in honour of Prof. James A. Matisoff. Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Linguistics Society. pp. 111–129.

- Donegan, Patricia; Stampe, David (2004). "Rhythm and the Synthetic Drift of Munda". In Singh, Rajendra (ed.). The Yearbook of South Asian Languages and Linguistics. De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 3–36.

- Newberry, J (2000). North Munda hieroglyphics. Victoria, BC: J Newberry.

- Śarmā, Devīdatta (2003). Munda: sub-stratum of Tibeto-Himalayan languages. Studies in Tibeto-Himalayan languages. Vol. 7. New Delhi: Mittal Publications. ISBN 81-7099-860-3.

- Varma, Siddheshwar (1978). Munda and Dravidian languages: a linguistic analysis. Hoshiarpur: Vishveshvaranand Vishva Bandhu Institute of Sanskrit and Indological Studies, Panjab University. OCLC 25852225.

- Zide, Norman H.; Anderson, G. D. S. (1999). Bhaskararao, P. (ed.). "The Proto-Munda Verb and Some Connections with Mon-Khmer". Working Papers International Symposium on South Asian Languages Contact and Convergence, and Typology. Tokyo: 401–421.

- Zide, Norman H.; Anderson, Gregory D. S. (2001). "The Proto-Munda Verb: Some Connections with Mon-Khmer". In Subbarao, K. V.; Bhaskararao, P. (eds.). Yearbook of South-Asian Languages and Linguistics. Delhi: Sage Publications. pp. 517–540. doi:10.1515/9783110245264.517.

- Anderson, Gregory D. S.; Zide, Norman H. (2001). "Recent Advances in the Reconstruction of the Proto-Munda Verb". In Brinton, Laurel J. (ed.). Historical Linguistics 1999: Selected papers from the 14th International Conference on Historical Linguistics, Vancouver, 9–13 August 1999. Current Issues in Linguistic Theory. Vol. 215. Amsterdam: Benjamins. pp. 13–30. doi:10.1075/cilt.215.03and. ISBN 978-90-272-3722-4.

- Jenny, Mathias; Weber, Tobias; Weymuth, Rachel (2014). "The Austroasiatic Languages: A Typological Overview". In Jenny, Mathias; Sidwell, Paul (eds.). The Handbook of Austroasiatic Languages. Leiden: Brill. pp. 13–143. doi:10.1163/9789004283572_003.

- Sidwell, Paul; Rau, Felix (2014). "Austroasiatic Comparative-Historical Reconstruction: An Overview". In Jenny, Mathias; Sidwell, Paul (eds.). The Handbook of Austroasiatic Languages. Leiden: Brill. pp. 221–363. ISBN 978-90-04-28295-7.

- Peterson, John M. (2011a). A Grammar of Kharia: A South Munda Language. Brill. ISBN 978-9-00418-720-7. OCLC 31045692.

- Peterson, John M. (2011b). ""Words" in Kharia: Phonological, morpho-syntactic and "orthographical" aspect". In Heig, Geoffrey; Nau, Nicole; Schnell, Stefan; Wegener, Claudia (eds.). Documenting Endangered Languages, Achievements and perspectives. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 89–119. doi:10.1515/9783110260021.89.

- Peterson, John M. (2015). "Introduction – advances in the study of Munda languages". Journal of South Asian Languages and Linguistics. 2 (2): 149–162. doi:10.1515/jsall-2015-0008.

- Alves, Mark J. (2020). "Morphology in Austroasiatic Languages". In Lieber, Rochelle (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Morphology. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.532.

- Hock, Hans Henrich; Bashir, Elena, eds. (2016). The Languages and Linguistics of South Asia: A Comprehensive Guide. Volume 7 of The World of Linguistics. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. doi:10.1515/9783110423303. ISBN 3-11-0423-383.

- Anderson, Gregory D. S. (2016). "Austroasiatic languages of South Asia". In Hock, Hans Henrich; Bashir, Elena (eds.). The Languages and Linguistics of South Asia: A Comprehensive Guide. Volume 7 of The World of Linguistics. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. pp. 107–130. doi:10.1515/9783110423303-003.

- Osada, Toshiki (2008). "Mundari". The Munda Languages. New York: Routledge. pp. 99–164. ISBN 0-415-32890-X.

- Zide, Norman H. (2008). "Korku". The Munda Languages. New York: Routledge. pp. 256–298. ISBN 0-415-32890-X.

- Hildebrandt, Kristine; Anderson, Gregory D. S. (2023). "Word Prominence in Languages of Southern Asia". In Hulst, Harry van der; Bogomolets, Ksenia (eds.). Word Prominence in Languages with Complex Morphologies. Oxford University Press. pp. 520–564. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198840589.003.0017.

- Anderson, Gregory D. S. (2014). "Overview of the Munda languages". In Jenny, Mathias; Sidwell, Paul (eds.). The Handbook of Austroasiatic Languages. Leiden: Brill. pp. 364–414. doi:10.1163/9789004283572_006.

- Jenny, Mathias (2020). "Verb-Initial Structures in Austroasiatic Languages". In Jenny, Mathias; Sidwell, Paul; Alves, Mark (eds.). Austroasiatic Syntax in Areal and Diachronic Perspective. Brill. pp. 21–45. doi:10.1163/9789004425606_003.

- Anderson, Gregory D. S. (2020). "Proto-Munda Prosody, Morphotactics and Morphosyntax in South Asian and Austroasiatic Contexts". In Jenny, Mathias; Sidwell, Paul; Alves, Mark (eds.). Austroasiatic Syntax in Areal and Diachronic Perspective. Brill. pp. 157–197. doi:10.1163/9789004425606_008.

- Rau, Felix (2020). "The Proto-Munda Predicate and the Austroasiatic Language Family". In Jenny, Mathias; Sidwell, Paul; Alves, Mark (eds.). Austroasiatic Syntax in Areal and Diachronic Perspective. Brill. pp. 198–235. doi:10.1163/9789004425606_009.

- Kobayashi, Masato; Mohan, Shailendra (2021). "Munda Languages: An Overview". In Mohan, Shailendra (ed.). Advances in Munda Linguistics. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 1–22. ISBN 1527570479.

- Anderson, Gregory D. S. (2021). "On the Role of Areal and Genetic Factors in the Development of the Word-Structure and Morphosyntax of the Munda Languages". In Mohan, Shailendra (ed.). Advances in Munda Linguistics. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 22–77. ISBN 1527570479.

- Ghosh, Arun (2021). "Infixation in Munda and its Austroasiatic Legacy". In Mohan, Shailendra (ed.). Advances in Munda Linguistics. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 78–107. ISBN 1527570479.

- Historical migrations

- Blench, Roger (19 July 2019). The Munda maritime dispersal: when, where and what is the evidence? (PDF) (Report).

- Rau, Paul; Sidwell, Felix (2019). The Maritime Munda Hypothesis. ICAAL 8, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 29–31 August 2019. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3365316.

- Rau, Felix; Sidwell, Paul (2019). "The Maritime Munda Hypothesis". Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society. 12 (2): 31–53. hdl:10524/52454.

External links

[edit]- SEAlang Munda Languages Project

- Donegan & Stampe Munda site

- Munda languages at Living Tongues

- bibliography

- The Ho language webpage by K. David Harrison, Swarthmore College

- RWAAI (Repository and Workspace for Austroasiatic Intangible Heritage)

- http://hdl.handle.net/10050/00-0000-0000-0003-66EE-3@view Munda languages in RWAAI Digital Archive